Pagina Principale

👋 Benvenuto in gb-asm-tutorial! Questo tutorial ti insegnerà come programmare giochi per il Game Boy e per il Game Boy Color.

While the Game Boy and Game Boy Color are almost the same console, the Game Boy Advance is entirely different. However, the GBA is able to run GB and GBC games! If you are looking to program GBC games and run them on a GBA, you’re at the right place; however, if you want to make games specifically for the GBA, please check out the Tonc tutorial instead.

Comandi

In cima alla pagina puoi vedere alcune icone, sempre presenti se ne dovessi avere bisogno!

- The “burger” toggles the navigation side panel;

- The brush allows selecting a different color theme;

- The magnifying glass pops up a search bar;

- The world icon lets you change the language of the tutorial;

- The printer gives a single-page version of the entire tutorial, which you can print if you want;

- The GitHub icon links to the tutorial’s source repository;

- The edit button allows you to suggest changes to the tutorial, provided that you have a GitHub account.

Ci sono anche delle frecce a lato della pagina (o in fondo, se sei su cellulare) per passare alla pagina successiva o precedente.

E con questo, per iniziare ti basterà premere la freccia a destra :)

Autori

Il tutorial è stato scritto da Eldred “ISSOtm” Habert, Evie, Antonio Vivace, LaroldsJubilantJunkyard e altri collaboratori.

Contribuire

You can provide feedback or send suggestions in the form of Issues on the GitHub repository.

We’re also looking for help for writing new lessons and improving the existing ones! You can go through the Issues to see what needs to be worked on and send Pull Requests!

You can also help translating the tutorial on Crowdin.

Licenza

In breve:

- Code within the tutorial is essentially public domain, meaning that you are allowed to copy it freely without restrictions.

- You are free to copy the tutorial’s contents (prose, diagrams, etc.), modify them, and share that, but you must give credit and license any copies under the same license.

- This site’s source code can be freely copied, but you must give a license and copyright notice.

Maggiori Informazioni, per maggiori informazioni sulle rispettive licenze, seguire questi link:

- All the code contained within the tutorial itself is licensed under CC0. To the extent possible under law, all copyright and related or neighboring rights to code presented within GB ASM Tutorial have been waived.

- The contents (prose, images, etc.) of this tutorial are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

- Code used to display and format the site is licensed under the MIT License unless otherwise specified.

Tabella di marcia

The tutorial is split into three parts. We strongly advise you go through the tutorial in order!

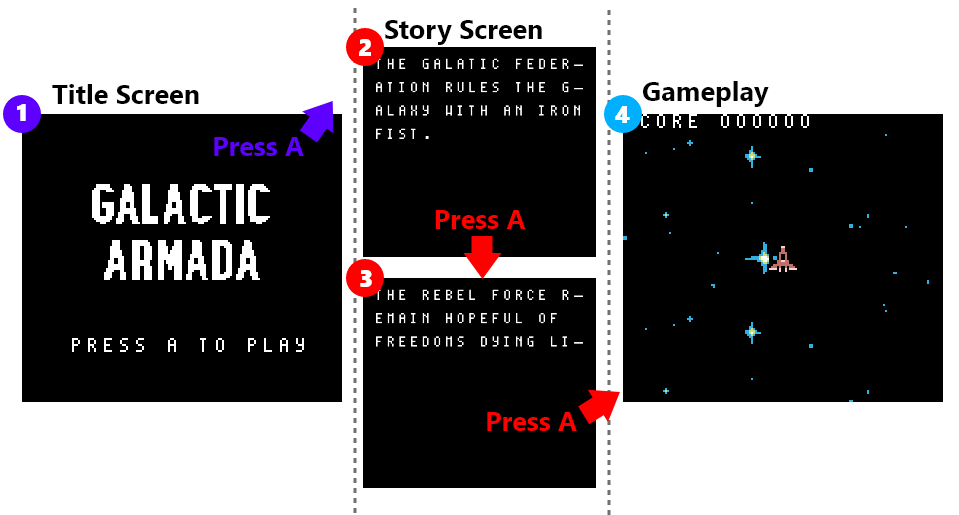

Nella parte Ⅰ, lanciamo il nostro primo programma “Hello World!”, per poi analizzarlo al fine di capire come funziona il Game Boy.

Nella parte Ⅱ programmiamo il nostro primo gioco, un clone di Arkanoid; impariamo a dare le prime istruzioni all’hardware per ottenere qualcosa che si possa definire “gioco”. Lungo il percorso commetteremo molti errori, ma questo servirà anche a imparare a risolvere i problemi del nostro codice.

Infine, la Parte Ⅲ riguarda l’uso “avanzato” dell’hardware, dove impareremo a creare giochi ancora più rifiniti e programmeremo uno “Shoot ’Em Up”!

Questo tutorial è ancora in lavorazione.

Aiuto

We hope this tutorial will work for you.

But if it doesn’t (the format may not work well for everyone, and that’s okay), we encourage to look at some other resources, which might work better for you.

It’s also fine to take a break from time to time; feel free to read at your own pace.

If you are stuck in a certain part of the tutorial, want some advice, or just wish to chat with us, the GBDev community chat is the place to go!

The authors actively participate there so don’t be afraid to ask questions!

The #asm channel should be the most appropriate to discuss the tutorial.

Se preferisci la posta elettronica, puoi raggiungerci all’indirizzo tutorial@<domain>, devi sostituire <domain> con il nome di dominio di questo sito.

Si tratta di una misura antispam, spero che tu capisca.

Preparazione

Per prima cosa, dobbiamo configurare il nostro ambiente di sviluppo. Avremo bisogno di:

- A POSIX environment

- RGBDS v0.5.1 (though v0.5.0 should be compatible)

- GNU Make (preferably a recent version)

- A code editor

- A debugging emulator

❓😕

The following install instructions are provided on a “best-effort” basis, but may be outdated, or not work for you for some reason. Don’t worry, we’re here to help: ask away, and we’ll help you with installing everything!

Strumenti

Linux e macOS

Buone notizie: hai già completato il primo passo! Dovete solo installare RGBDS e forse aggiornare GNU Make.

macOS

Al momento della stesura di questo articolo, macOS (fino alla 11.0, l’ultima release attuale) ha in dotazione un GNU Make molto datato.

È possibile verificarlo aprendo un terminale ed eseguendo make --version, che dovrebbe indicare “GNU Make” e una data, tra le altre cose.

Se il vostro Make è troppo vecchio, potete aggiornarlo usando la formula di Homebrew make.

Al momento in cui scriviamo, dovrebbe essere stampato un avviso che il Make aggiornato è stato installato come gmake; si può seguire il suggerimento di usarlo come make “predefinito”, oppure usare gmake invece di make in questo tutorial.

Linux

Una volta installato RGBDS, aprite il terminale ed eseguite il comando make --version per controllare la vostra versione di Make (che probabilmente è GNU Make).

Se make non è presente, potrebbe essere necessario installare le build-essentials della propria distribuzione.

Windows

The modern tools we’ll be using for Game Boy development have been designed for a Unix environment, so setup on Windows is not fully straightfoward. However, it’s possible to install an environment that will provide everything we need.

On Windows 10 and Windows 11, your best bet is WSL, which is a method for running a Linux distribution within Windows. Install WSL, then a distribution of your choice (pick Ubuntu if unsure), and then follow these steps again, but for the Linux distribution you installed.

In alternativa a WSL, si può usare MSYS2 o Cygwin; per poi consultare le istruzioni per l’installazione di Windows di [RGBDS] (https://rgbds.gbdev.io/install). Per quanto ne so, entrambi dovrebbero fornire una versione sufficientemente aggiornata di GNU Make.

Se avete programmato per altre console, come il GBA, controllate che MSYS2 non sia già installato sul vostro computer. Questo perché devkitPro, un popolare pacchetto di sviluppo homebrew, include MSYS2.

Editor di codice

Qualsiasi editor di codice va bene; personalmente uso Sublime Text con il suo pacchetto sintassi RGBDS; tuttavia è possibile usare qualsiasi editor di testo, compreso il Blocco Note se si è abbastanza pazzi. Awesome GBDev ha una sezione sui pacchetti per l’evidenziazione della sintassi dove potete controllare se il vostro editor preferito supporta RGBDS.

Emulatore

Using an emulator to play games is one thing; using it to program games is another. The two aspects an emulator must fulfill to allow an enjoyable programming experience are:

- Debugging tools:

When your code goes haywire on an actual console, it’s very difficult to figure out why or how.

There is no console output, no way to

gdbthe program, nothing. However, an emulator can provide debugging tools, allowing you to control execution, inspect memory, etc. These are vital if you want GB dev to be fun, trust me! - Good accuracy:

Accuracy means “how faithful to the original console something is”.

Using a bad emulator for playing games can work (to some extent, and even then…), but using it for developing a game makes it likely to accidentally render your game incompatible with the actual console.

For more info, read this article on Ars Technica (especially the

An emulator for every game

section at the top of page 2). You can compare GB emulator accuracy on Daid’s GB-emulator-shootout.

The emulator I will be using for this tutorial is Emulicious. Users on all OSes can install the Java runtime to be able to run it. Other debugging emulators are available, such as Mesen2, BGB (Windows/Wine only), SameBoy (graphical interface on macOS only); they should have similar capabilities, but accessed through different menu options.

Hello World!

In questa lezione inizieremo ad assemblare il nostro primo programma. Il resto del capitolo sarà dedicato a spiegare come e perché funziona.

Tenete presente che da ora dovremo lanciare molti comandi, quindi è il momento di aprire una finestra del terminale.

È buon norma creare una nuova directory (mkdir gb_hello_world, per esempio, poi cd gb_hello_world per entrare nella nuova directory).

Grab the following files (right-click each link, “Save Link As…”), and place them all in this new directory:

Quindi, sempre dal terminale, all’interno di quella directory, lanciate i tre comandi seguenti.

CONVENTION

To make it clear where each command begins, they are preceded by a $ symbol. However, do not type it when entering them in your shell!

rgbasm -o hello-world.o hello-world.asm

rgblink -o hello-world.gb hello-world.o

rgbfix -v -p 0xFF hello-world.gb

‼️

Fate attenzione agli argomenti! Alcune opzioni, come -o, usano l’argomento dopo di esse come parametro:

rgbasm -o hello-world.asm hello-world.owon’t work (and may corrupthello-world.asm!)rgbasm hello-world.asm -o hello-world.owill work

In caso di spazi all’interno di un argomento, è necessario metterlo tra virgolette:

rgbasm -o hello world.o hello world.asmwon’t workrgbasm -o "hello world.o" "hello world.asm"will work

It should look like this:

(Se riscontrate un errore che non riuscite a risolvere da soli, non abbiate paura di chiedere! Lo risolveremo insieme)

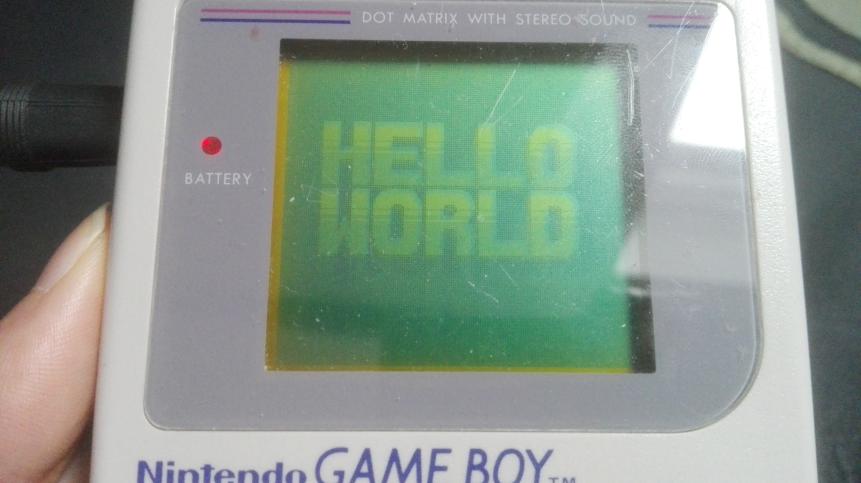

Congrats!

You just assembled your first Game Boy ROM!

Now, we just need to run it; open Emulicious, then go “File”, then “Open File”, and load hello-world.gb.

Potreste anche prendere una flash cart (cartuccia flash) (io uso l’EverDrive GB X5, ma ci sono molte alternative), caricarci la vostra ROM e farla girare su una console vera e propria!

Bene, ora che abbiamo qualcosa che funziona, è il momento di togliere le tende per scoprire cosa c’è sotto…

Strumenti di lavoro

Dunque, nella lezione precedente abbiamo scritto una piccola ROM “Hello World!”. Ora è il momento di capire meglio cosa abbiamo fatto.

RGBASM e RGBLINK

Iniziamo spiegando cosa fanno rgbasm e rgblink.

RGBASM è un assembler (compilatore).

Il suo compito è leggere il codice sorgente (nel nostro caso hello-world.asm e hardware.inc) e generare un file di codice che però è incompleto:

RGBASM non sempre ha tutte le informazioni che gli servono a generare una ROM, quindi produce dei file oggetto che fanno da intermediari (con estensione .o).

RGBLINK è un linker. Il suo compito è usare le informazioni dei file oggetto (che nel nostro caso è solo uno) ed unirli (in inglese “link”) in una ROM. RGBLINK potrebbe sembrare superfluo, ma è solo perché la ROM che abbiamo guardato è davvero piccola: quando nella seconda parte il nostro progetto crescerà, la sua utilità sarà più apparente.

Quindi: Codice sorgente → rgbasm → File oggetto → rgblink → ROM, giusto?

Beh, non esattamente.

RGBFIX

RGBLINK does produce a ROM, but it’s not quite usable yet. See, actual ROMs have what’s called a header. It’s a special area of the ROM that contains metadata about the ROM; for example, the game’s name, Game Boy Color compatibility, and more. For simplicity, we defaulted a lot of these values to 0 for the time being; we’ll come back to them in Part Ⅱ.

However, the header contains three crucial fields:

- The Nintendo logo,

- the ROM’s size,

- and two checksums.

Quando la console viene accesa viene eseguito un programma chiamato ROM di avvio (boot ROM) responsabile, tra l’altro, dell’animazione di avvio leggendo il logo di Nintendo dalla ROM. Alla fine dell’animazione, però, la ROM di avvio controlla che il logo di Nintendo sia corretto, e interrompe l’esecuzione se non lo è: in pratica, se non azzecchiamo il logo il nostro gioco non partirà mai… 😦 Questo meccanismo era per evitare la pirateria; per nostra fortuna, però, non è più valida perciò non dobbiamo preoccuparci! 😄

Allo stesso modo, la ROM di avvio calcola anche un checksum dell’header, presumibilmente per garantire che non sia corrotto. L’header contiene anche una copia di questo checksum; se non corrisponde a quello calcolato dalla ROM di avvio, la ROM di avvio si blocca!

L’header contiene anche un checksum dell’intera ROM, ma non viene mai utilizzato. Non costa niente ed è una buona idea, comunque, farlo bene.

Infine, l’header contiene anche la dimensione della ROM, necessaria per emulatori e dalle flash cart.

RGBFIX serve proprio a compilare l’header in automatico, in particolare questi tre campi senza i quali il GameBoy non farà funzionare il gioco.

L’opzione -v dice a RGBFIX di rendere valido l’header, inserendo il logo e calcolando le checksum.

L’opzione -p 0xFF invece aggiunge dei byte alla ROM finché non raggiunge una dimensione valida (in inglese padding), per poi scriverla nell’header.

Perfetto!

Quindi, per riassumere:

codice sorgente → rgbasm → file oggetto → rgblink → ROM “vera” → rgbfix → ROM funzionante

A questo punto ti potresti chiedere: perché non si uniscono tutti questi programmi in uno solo?

Ci sono ragioni nella storia di questi programmi, ma soprattutto RGBLINK può fare altro (per esempio usando -x), e a volte RGBFIX è usato senza che RGBLINK sia minimamente necessario.

Nomi dei file

A RGBDS, come alla maggior parte dei programmi, non importa come chiami i file né l’estensione che gli dai: l’importante è il contenuto.

Per esempio molti usano l’estensione .s per il sorgente, oppure .obj per gli oggetti.

Binario ed esadecimale

Prima di passare al codice dobbiamo introdurre alcuni concetti.

Quando si programma ad un basso livello è fondamentale capire bene i sistemi binario ed esadecimale. Se già conoscessi questi concetti, in fondo alla pagina ci sono delle informazioni specifiche all’uso di RGDBS.

Cos’è il binario? È semplicemente un modo alternativo di rappresentare i numeri, in base 2. Noi contiamo in base 10, ovvero con 10 cifre: 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, e 9. Le cifre hanno una funzione ben specifica:

42 = 4 × 10 + 2

= 4 × 10^1 + 2 × 10^0

↑ ↑

These tens come from us counting in base 10!

1024 = 1 × 1000 + 0 × 100 + 2 × 10 + 4

= 1 × 10^3 + 0 × 10^2 + 2 × 10^1 + 4 × 10^0

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

And here we can see the digits that make up the number!

CONVENTION

^ qui significa “alla potenza di”, dove X^N è uguale a moltiplicare X con se stesso N volte, e X ^ 0 = 1.

Con le cifre decimali ogni numero viene scomposto in maniera univoca in potenze di 10 (il decimale è la base 10, ricordi?). Ma perché fermarsi alle potenze di 10? Potremmo invece usare altre basi, come la base 2 (il perché della base 2 sarà spiegato più avanti).

Il sistema binario è in base 2, quindi ha solo due cifre (chiamate bit): 0 e 1. Possiamo quindi generalizzare il principio descritto sopra e riscrivere i due numeri di prima in modo simile:

42 = 1 × 32 + 0 × 16 + 1 × 8 + 0 × 4 + 1 × 2 + 0

= 1 × 2^5 + 0 × 2^4 + 1 × 2^3 + 0 × 2^2 + 1 × 2^1 + 0 × 2^0

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

And since now we're counting in base 2, we're seeing twos instead of tens!

1024 = 1 × 1024 + 0 × 512 + 0 × 256 + 0 × 128 + 0 × 64 + 0 × 32 + 0 × 16 + 0 × 8 + 0 × 4 + 0 × 2 + 0

= 1 × 2^10 + 0 × 2^9 + 0 × 2^8 + 0 × 2^7 + 0 × 2^6 + 0 × 2^5 + 0 × 2^4 + 0 × 2^3 + 0 × 2^2 + 0 × 2^1 + 0 × 2^0

↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑ ↑

Quindi, applicando lo stesso principio, possiamo dire che in base 2, 42 si scrive come 101010 e 1024 come 10000000000.

Poiché non è possibile distinguere tra dieci (10 decimale) e due (10 binario), l’assemblaggio RGBDS prevede numeri binari preceduti da un segno di percentuale: 10 è dieci e %10 è due.

Ok, ma perché proprio la base 2? Visto che un bit può essere solo 0 o 1, è molto facile rappresentarlo: può essere “ON” o “OFF”, vuoto o pieno, ecc! Se ad esempio si vuole creare una memoria da un bit basta prendere una scatola: se è vuota allora simboleggia uno 0; se contiene qualcosa, allora è un 1. I computer manipolano quindi principalmente numeri binari e questo ha molte implicazioni, come vedremo nel corso di questo tutorial.

Esadecimale

Ricapitolando: il decimale non è pratico per i computer, che si affidano invece ai numeri binari (base 2). Ok, ma il binario è davvero difficile da usare per noi programmatori. Prendiamo %10000000000, ovvero 2048; mentre per scriverlo in decimale bastano solo 4 cifre, in binario ne servono 12! E probabilmente non avete neanche notato che ho scritto uno zero di troppo! Per fortuna arriva l’esadecimale a salvare la situazione! 🦸

La base 16 funziona esattamente come tutte le altre basi, ma con 16 cifre (chiamate “nibbles” in inglese): 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, A, B, C, D, E, ed F.

42 = 2 × 16 + 10

= 2 × 16^1 + A × 16^0

1024 = 4 × 256 + 0 × 16 + 0

= 4 × 16^2 + 0 × 16^1 + 0 × 16^0

Come per il binario useremo un prefisso per indicare l’esadecimale, cioè $.

Quindi, 42 = $2A e 1024 = $400.

Questo è molto più compatto del binario, e anche un po’ più del decimale; ma ciò che rende l’esadecimale molto interessante è che una sua cifra corrisponde esattamente a 4 bit!

| Nibble | Bits |

|---|---|

| $0 | %0000 |

| $1 | %0001 |

| $2 | %0010 |

| $3 | %0011 |

| $4 | %0100 |

| $5 | %0101 |

| $6 | %0110 |

| $7 | %0111 |

| $8 | %1000 |

| $9 | %1001 |

| $A | %1010 |

| $B | %1011 |

| $C | %1100 |

| $D | %1101 |

| $E | %1110 |

| $F | %1111 |

Ciò rende facilissimo convertire tra binario ed esadecimale, e mantenere una notazione sufficientemente compatta. Per questo, l’esadecimale è molto più utilizzato del binario. E non preoccuparti, puoi ancora usare il decimale 😜

(Nota: si potrebbe pensare che anche l’ottale, cioè la base 8, funzioni altrettanto bene; tuttavia avremo a che fare perlopiù con unità di 8 bit, per le quali l’esadecimale funziona molto meglio dell’ottale. Volendo, RGBDS permette di usare l’ottale tramite il prefisso &, ma non l’ho mai visto usare nella pratica)

If you’re having trouble converting between decimal and binary/hexadecimal, check whether your favorite calculator program has a ‘programmer’ mode or a way to convert between bases.

Riepilogo

- In RGBDS assembly, the hexadecimal prefix is

$, and the binary prefix is%. - Hexadecimal can be used as a “compact binary” notation.

- Using binary or hexadecimal is useful when individual bits matter; otherwise, decimal works just as well.

- For when numbers get a bit too long, RGBASM allows underscores between digits (

123_465,%10_1010,$DE_AD_BE_EF, etc.)

Registri

Alright! Now that we know what bits are, let’s talk about how they’re used. Don’t worry, this is mostly preliminary work for the next section, where we will—finally!—look at the code 👀

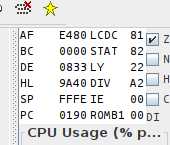

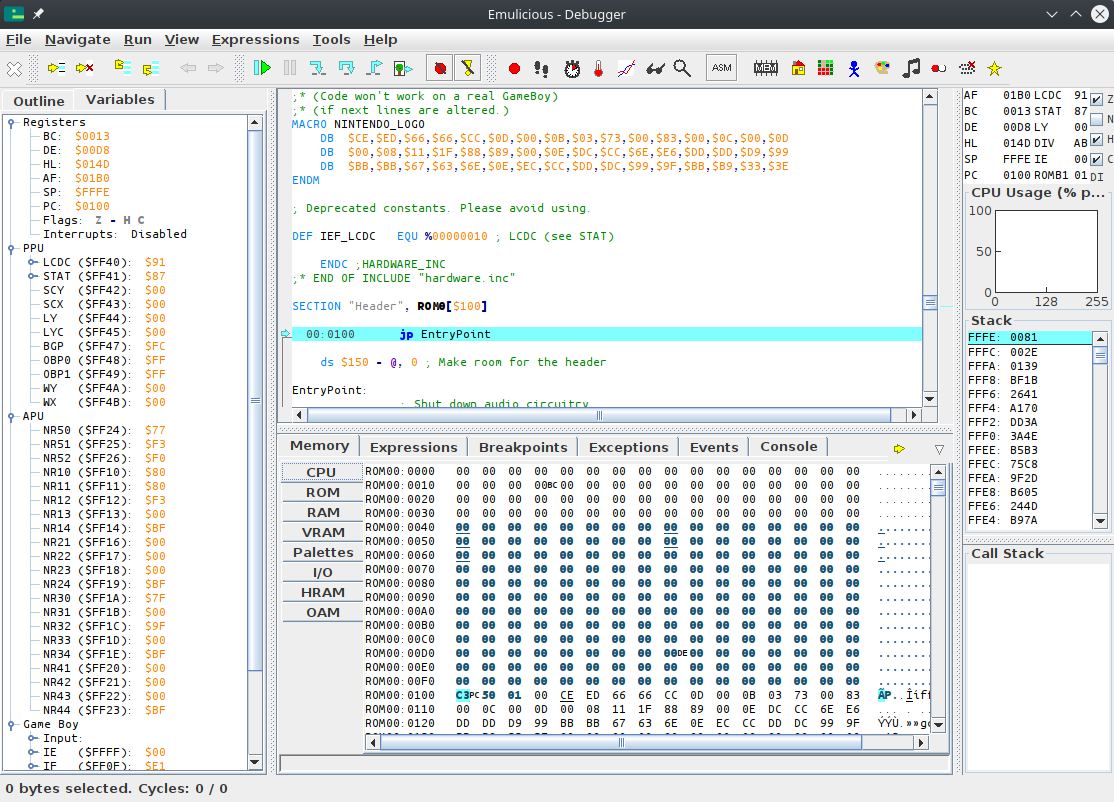

First, if you opened Emulicious, you have been greeted with just the Game Boy screen. So, it’s time we pop the debugger open! Go to “Tools”, then click “Debugger”, or press F1. Then in the debugger’s menu, click “View”, then click “Show Addresses”

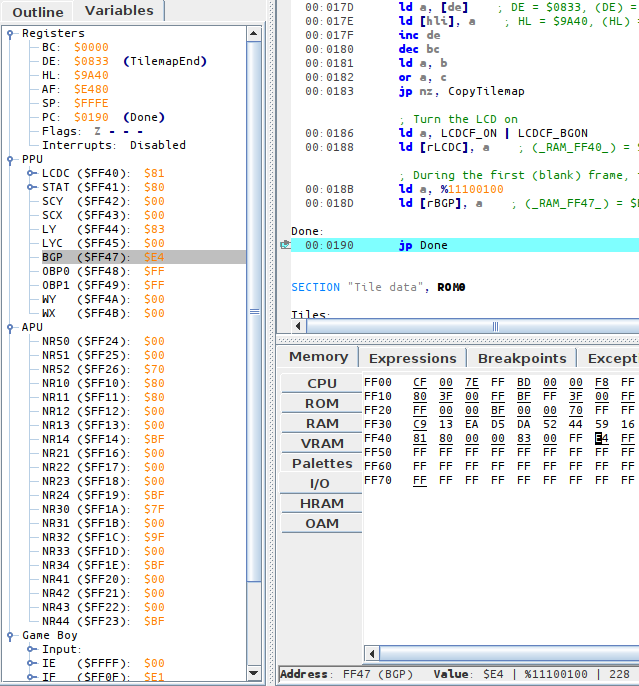

Il debugger potrebbe sembrare incomprensibile all’inizio, ma non ti preoccupare: ti ci abituerai in fretta! Per il momento guarda in alto a destra, dove c’è un piccolo spazio intitolato register viewer (visualizzatore dei registri).

⚠️

Il visualizzatore mostra sia i registri della CPU che alcuni registri hardware. In questa lezione parleremo solo dei registri della CPU, perciò non ti preoccupare se salteremo alcuni nomi.

Ma cosa sono questi registri della CPU? Ti faccio un esempio: immagina di star preparando una torta. Ovviamente avrai una ricetta da seguire, come ad esempio “sciogli 125g di cioccolato e 125g di burro, mescola il tutto con due uova” e così via. Dopo aver preso gli ingredienti, non li usi direttamente nel frigo; per comodità, li prenderai e li metterai su un banco da lavoro o un tavolo dove lavorarci più facilmente.

I registri sono questo tavolo, su cui il processore poggia temporaneamente i suoi ingredienti. Più concretamente, sono dei piccoli spazi di memoria (Il GameBoy ne ha solo 10 byte, e anche le CPU moderne hanno meno di un kilobyte se non si contano i registri SIMD). Eseguire le operazioni direttamente sulla memoria è scomodo, sarebbe come rompere le uova nel frigo: per questo le spostiamo sul tavolo, i registri, prima di romperle.

ℹ️

Ovviamente ci sono eccezioni a questa regola, come un po’ tutte le regole che ti spiegheremo nel tutorial; stiamo semplificando di molto le cose per mantenerle ad un livello abbastanza facile da comprendere, perciò non prendere mai queste regole troppo alla lettera.

Registri Generici

A grandi linee ci sono due tipi di registri: registri generici e registri speciali. Un registro generico (abbreviato GPR) può essere usato per dati di qualunque tipo. Qualche GPR ha anche delle funzioni più specifiche, come vedremo più in là; in generale per distinguerli da quelli speciali chiediti “posso inserirci dati arbitrari?”.

Parleremo poi dei registri speciali; hanno funzioni particolari che non abbiamo ancora spiegato e perciò li spiegheremo quando parleremo della funzione specifica, visto che fino ad allora non ne capiremmo lo scopo.

La CPU del Game Boy ha sette GPR a 8 bit: a, b, c, d, e, h e l.

“8 bit” significa che memorizzano 8 bit.

Pertanto, possono memorizzare numeri interi da 0 a 255 (%1111_1111 alias $FF).

`a’ è l’accumulatore, e come vedremo più avanti può essere usato in modi particolari.

Questi registri hanno un’altra caratteristica interessante; sono tutti (tranne a) accoppiati ad un altro registro, e queste coppie possono funzionare da registri a 16 bit: BC, DE, e HL.

Ma tieni sempre a mente che le coppie non sono indipendenti dai registri che li formano; se, ad esempio, D contiene 192 ($C0) ed E 222 ($DE) allora DE conterrà 49374 ($C0DE) = D × 0x100 + E.

Tutte le altre coppie funzionano allo stesso modo.

Quindi, cambiare il valore di DE modifica sia quello di D che di E allo stesso tempo e modificare D o E cambierà il valore della coppia DE.

Ok, ma come facciamo a usare questi registri?

È il momento di dare un’occhiata all’Assembly!

Primi passi in Assembly

Bene, ora che sappiamo cosa fanno gli strumenti, vediamo che lingua parla RGBASM.

Prenderò una breve porzione dell’inizio di hello-world.asm, in modo da essere d’accordo sui numeri di riga e da avere un’evidenziazione della sintassi anche se il vostro editor non la supporta.

INCLUDE "hardware.inc"

SECTION "Header", ROM0[$100]

jp EntryPoint

ds $150 - @, 0 ; Make room for the header

EntryPoint:

; Shut down audio circuitry

ld a, 0

ld [rNR52], a

Analizziamolo insieme. Sappi che per il momento salteremo molte delle funzionalità di RGBASM; se fossi curioso di saperne di più, dovrai aspettare fino alla seconda o terza parte oppure leggere la documentazione.

Commenti

Iniziamo dalla riga 10, che dovrebbe essere grigia nel riquadro qui sopra.

I punti e virgola ; indicano un commento.

I commenti (che finiscono alla fine della riga) sono ignorati dall’assembler, indipendentemente dal contenuto.

Come vedi alla riga 7, puoi anche inserire commenti dopo aver scritto altro.

I commenti sono molto importanti in tutti i linguaggi di programmazione: ti aiutano a descrivere la funzione del tuo codice. È più o meno la differenza tra “scalda il forno fino a 180°C” e “scalda il forno a 180°C, se lo scaldassi di più la torta brucerebbe”. I commenti sono utilissimi in ogni linguaggio di programmazione, ma in Assembly sono ancora più importanti: infatti, il codice Assembly è molto più astratto.

Istruzioni

Assembly is a very line-based language. Each line can contain one of two things:

- a directive, which instructs RGBASM to do something, or

- an instruction1, which is written directly into the ROM.

Parleremo delle direttive più avanti, per ora concentriamoci sulle istruzioni: per esempio, nello snippet qui sopra, ignoreremo le righe 1 (INCLUDE), 7 (ds) e 3 (SECTION).

Per continuare l’analogia con la preparazione di una torta, le istruzioni sono come i passi di una ricetta. Il processore (CPU) esegue un’istruzione alla volta. Istruzione dopo istruzione… dopo un po’ si arriva al risultato! Come cuocere una torta, disegnare “Hello World”, oppure mostrarti un tutorial sull’Assembly del GameBoy!

Le istruzioni sono composte da una mnemonica, un nome con cui le puoi invocare, e dei parametri, ovvero su cosa va eseguita l’operazione. Ad esempio: in “sciogli il cioccolato ed il burro in una padella” l’istruzione è tutta la frase; la mnemonica sarebbe l’azione, ovvero sciogli, mentre i parametri sono gli oggetti della frase (cioccolato, burro, padella).

Cominciamo dall’istruzione più importante: ld.

ld sta per “carica”, e semplicemente copia i dati contenuti nel secondo parametro (“RHS”) nel primo (“LHS”).

Per esempio, guardiamo la riga 11 del nostro programma, ld a, 0: copia (“carica”) il numero zero nel registro a2.

Per fare un altro esempio, a riga 33 troviamo ld a, b: significa semplicemente “copia il valore di b in a.

| Instruction | Mnemonic | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Load | ld | Copies values around |

ℹ️

Per via delle limitazioni del processore, non tutte le combinazioni di operandi sono valide per ld e per molte altre istruzioni; ne parleremo in seguito, quando arriverà il momento di scrivere il nostro codice.

🤔

RGBDS ha una lista delle istruzioni del GameBoy che vale la pena tenere tra i preferiti, e che si può anche consultare dal terminale scrivendo man 7 gbz80 se RGBDS è installato sulla propria macchina (tranne su Windows…).

Le descrizioni che trovate in quella pagina sono più concise: sono intese come un promemoria, non come un tutorial.

Direttive

Quindi, in un certo senso, le istruzioni sono destinate al processore del GameBoy mentre i commenti sono destinati al programmatore. Ma alcune righe non sono né l’una né l’altra cosa, e sono invece dei metadati destinati a RGBDS stesso. Queste sono chiamate direttive e il nostro “Hello World” ne contiene tre.

Includere un altro file

INCLUDE "hardware.inc"

La riga 1 include hardware.inc3.

Includendo un file è come se copiassimo il suo contenuto alla riga dove inseriamo la direttiva.

Così facendo, si può riciclare facilmente il codice in diversi file: se, ad esempio, due file a.asm e b.asm includono hardware.inc basta modificare il file perché le modifiche si applichino ad a.asm e b.asm.

Se invece copiassi a mano il contenuto di hardware.inc in a.asm e b.asm dovresti modificare il contenuto di entrambi ogni volta che vuoi apportare un cambiamento, che non è solo uno spreco di tempo ma aumenta la possibilità di commettere errori.

hardware.inc definisce alcune costanti molto utili per interfacciarsi con l’hardware del GameBoy.

Le costanti non sono altro che dei nomi a cui è assegnato un valore: scrivere una costante equivale a scrivere il valore che le è assegnato.

Questo torna molto utile: è molto più semplice ricordare il registro “LCD Control” (impostazioni dello schermo) col nome rLCDC piuttosto che ricordare l’indirizzo $FF40.

Parleremo delle costanti in modo più approfondito nella Parte Ⅱ.

Sezioni

Spieghiamo innanzitutto che cos’è una “sezione”, poi vedremo che cosa fa la riga 3.

Una sezione rappresenta un intervallo contiguo di memoria che, di base, finisce da qualche parte non nota in anticipo.

Se si vuole vedere dove finisce ogni sezione si può chiedere a RGBLINK di generare un “file mappa” con l’opzione -m:

rgblink hello-world.o -m hello-world.map

…e possiamo vedere, per esempio, dove è finita la sezione "Tilemap":

SECTION: $05a6-$07e5 ($0240 bytes) ["Tilemap"]

Le sezioni non possono essere divise da RGBDS, che è utile ad esempio per il codice poiché il processore esegue le istruzioni una dopo l’altra (a parte con i salti, che vedremo più avanti). Va trovato il giusto equilibrio per il numero di sezioni: non troppe ma neanche troppo poche, anche se in genere non ha molta importanza fino a quando non si inizia a parlare di banche di memoria.

Quindi, per ora, assumiamo che una sezione debba contenere cose che “vanno insieme” dal punto di vista topico, ed esaminiamo una delle nostre.

SECTION "Header", ROM0[$100]

Quindi!

Cosa fa questa riga?

Altro non è che la dichiarazione di una nuova sezione; tutte le istruzioni e i dati dopo questa riga e fino alla successiva dichiarazione SECTION saranno inseriti in questa sezione appena creata.

Prima della prima direttiva SECTION non c’è una sezione “attiva”: scrivere dati o codice al di fuori di una sezione ci darà l’errore Cannot output data outside of a SECTION.

Il nome della nuova sezione è “Header”.

I nomi delle sezioni possono contenere qualsiasi carattere (e anche essere vuoti, se si vuole) e devono essere unici[^nome_sezione].

La parola chiave ROM0 indica a quale “tipo di memoria” appartiene la sezione (ecco un elenco).

Ne parleremo nella Parte Ⅱ.

Dove dice [100$] invece è più interessante, perché è un’indicazione speciale per questa sezione.

Se ricordi, prima abbiamo detto che:

a section […] by default, ends up somewhere not known in advance.

Però alcune parti della memoria sono speciali, e quindi a volte è necessario che una sezione specifica copra un intervallo di memoria specifico.

Per permetterlo, RGBASM ha la sintassi [addr] che forza l’indirizzo iniziale della sezione a essere addr.

In questo caso, l’intervallo di memoria $100-$14F è speciale perché è l’header della ROM. Parleremo dell’header tra un paio di lezioni, ma per il momento basta sapere che non dobbiamo inserire né codice né dati in quello spazio. E come facciamo? Innanzitutto, iniziamo una sezione all’indirizzo $100, dopodiché riserviamo un po’ di spazio.

Lasciare spazio

jp EntryPoint

ds $150 - @, 0 ; Make room for the header

La riga 7 afferma di “fare spazio per l’header”, di cui ho parlato brevemente poco sopra.

Per ora, concentriamoci su ciò che ds fa effettivamente.

ds è usato per allocare staticamente della memoria.

Riserva un certo numero di byte, che sono impostati ad un certo valore dato.

Il primo argomento di ds, in questo caso $150 - @, è quanti byte riservare.

Il secondo argomento (che è opzionale), in questo caso 0, è il valore a cui impostare ogni byte riservato4.

Vedremo perché questi byte devono essere riservati in un paio di lezioni.

È importante notare che il primo argomento è un’espressione.

RGBDS (fortunatamente!) supporta l’inserimento di espressioni arbitrarie pressoché ovunque.

Quest’espressione è una semplice sottrazione: $150 meno @, che è un simbolo speciale che sta per “l’indirizzo in memoria attuale”.

Un simbolo è essenzialmente “un nome associato a un valore”, di solito un numero. Nel corso dell’esercitazione esploreremo i diversi tipi di simboli, a partire dalle etichette nella prossima sezione.

Un simbolo numerico utilizzato in un’espressione viene sostituito dal suo valore, che dev’essere noto al momento della compilazione della ROM; in particolare, non può dipendere dal contenuto di alcun registro.

Ora vi starete chiedendo cosa siano questi “indirizzi di memoria” di cui continuo a parlare. Andiamo subito a scoprirlo!

-

Technically, instructions in RGBASM are implemented as directives, basically writing their encoded form to the ROM; but the distinction between the instructions in the source code and those in the final ROM is not worth bringing up right now. ↩

-

The curious reader may ask where the value is copied from. The answer is simply that the “immediate” byte ($00 in this example) is stored in ROM just after the instruction’s opcode byte, and it’s what gets copied to

a. We will come back to this when we talk about how instructions are encoded later on. ↩ -

hardware.incitself contains more directives, in particular to define a lot of symbols. They will be touched upon much later, so we won’t look intohardware.incyet. ↩ -

Actually, since RGBASM 0.5.0,

dscan accept a list of bytes, and will repeat the pattern for as many bytes as specified. It just complicates the explanation slightly, so I omitted it for now. Also, if the argument is omitted, it defaults to what is specified using the-poption to RGBASM. ↩

Memoria

🎉

Congratulazioni, avete appena finito le lezioni più difficili del tutorial! Dal momento che avete le basi, d’ora in poi vedremo codice sempre più concreto.

Se guardiamo alla riga 29 leggiamo ld a, [de].

Stando a quanto abbiamo appena appreso, questo copia un valore nel registro a… ma da dove?

Cosa significano queste parentesi?

Per rispondere dobbiamo parlare della memoria.

Cos’è una memoria?

Lo scopo della memoria è quello di immagazzinare informazioni. Su un foglio di carta o su una lavagna si possono scrivere lettere per memorizzare, ad esempio, la lista della spesa. Ma cosa si può memorizzare nella memoria di un computer? La risposta a questa domanda è corrente[^memoria_magnetica]. La memoria del computer è costituita da piccole celle in grado di immagazzinare corrente. Ma, come abbiamo visto nella lezione sul binario, la presenza o l’assenza di corrente può essere utilizzata per codificare i numeri binari!

Per farla breve: la memoria immagazzina numeri. Difatti la memoria è una lunga lista di numeri, memorizzati in celle. Per identificare in modo univoco ogni cella, le viene assegnato un numero (e che altro!) chiamato indirizzo. Come i numeri civici! La prima cella ha l’indirizzo 0, poi l’indirizzo 1, 2 e così via. Sul Game Boy ogni cella contiene 8 bit, cioè un byte.

Quante cellule ci sono? In realtà questa è una domanda trabocchetto…

I tanti tipi di memoria

There are several memory chips in the Game Boy, but we can put them into two categories: ROM and RAM 1. ROM simply designates memory that cannot be written to2, and RAM memory that can be written to.

Per via del loro funzionamento il processore ed i circuiti di memoria possono utilizzare un solo numero per gli indirizzi. Torniamo all’analogia dei “numeri civici”: ogni circuito di memoria è una strada, con la sua serie di numeri, ma il processore non ha idea di cosa sia una strada, si occupa solo di numeri civici. Per consentire al processore di parlare con più circuiti serve una sorta di “servizio postale”, il selezionatore di circuito (“chip selector” in inglese), che ha il compito di tradurre i numeri civici del processore in una via ed un numero civico effettivi.

For example, let’s say a convention is established where addresses 0 through 1999 go to chip A’s addresses 0–1999, 2000–2999 to chip B’s 0–999, and 3000–3999 to chip C’s 0–999. Then, if the CPU asks for the byte at address 2791, the chip selector will ask chip B for the byte at its own address 791, and forward the reply to the CPU.

Poiché gli indirizzi trattati dal processore non corrispondono direttamente a quelli dei circuiti si parla di indirizzi logici (qui, quelli del processore) e di indirizzi fisici (qui, quelli dei circuiti), e la corrispondenza è chiamata mappa di memoria (“memory map” in inglese). Poiché stiamo programmando il processore ci occuperemo solo di indirizzi logici, ma è fondamentale tenere presente che indirizzi diversi possono essere supportati da circuiti di memoria diversi, poiché ogni circuito ha caratteristiche uniche.

This may sound complicated, so here is a summary:

- Memory stores numbers, each 8-bit on the Game Boy.

- Memory is accessed byte by byte, and the cell being accessed is determined by an address, which is just a number.

- The CPU deals with all memory uniformly, but there are several memory chips each with their own characteristics.

Mappa di memoria del Game Boy

Adesso rispondiamo alla domanda che ci aveva portato a questa sezione: quante celle di memoria ci sono sul Game Boy? Ora possiamo riformulare meglio questa domanda come “quanti indirizzi logici ci sono?” o “quanti indirizzi fisici ci sono in totale?”.

Gli indirizzi logici, che sono solo numeri, sono a 16 bit sul Game Boy. Pertanto, ci sono 2^16 = 65536 indirizzi logici, da $0000 a $FFFF. Ma quanti sono gli indirizzi fisici? Ecco una mappa della memoria per gentile concessione di Pan Docs (anche se la semplificherò un po’):

| Start | End | Name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0000 | $7FFF | ROM | The game ROM, supplied by the cartridge. |

| $8000 | $9FFF | VRAM | Video RAM, where graphics are stored and arranged. |

| $A000 | $BFFF | SRAM | Save RAM, optionally supplied by the cartridge to save data to. |

| $C000 | $DFFF | WRAM | Work RAM, general-purpose RAM for the game to store things in. |

| $FE00 | $FE9F | OAM | Object Attribute Memory, where “objects” are stored. |

| $FF00 | $FF7F | I/O | Neither ROM nor RAM, but this is where you control the console. |

| $FF80 | $FFFE | HRAM | High RAM, a tiny bit of general-purpose RAM which can be accessed faster. |

| $FFFF | $FFFF | IE | A lone I/O byte that’s separated from the rest for some reason. |

$8000 + $2000 + $2000 + $2000 + $A0 + $80 + $7F + 1 fanno in totale $E1A0, ovvero 57760 byte di memoria che si possono effettivamente usare. E a questo punto potreste chiedervi: “E i restanti 7776 byte? Cosa succede quando provo ad usarli?”; la risposta è: “Dipende, è complicato; evitate di accedervi”.

Etichette

Ok, tutto questo è molto bello, ma non vi aspetterete certo che io tenga in mente tutti questi indirizzi per conto mio, giusto?? Beh, non temere, perché abbiamo le etichette!

Le etichette sono simboli che in pratica permettono di assegnare un nome a un indirizzo di memoria.

Un’etichetta viene dichiarata come alla riga 9 (EntryPoint:): all’inizio della riga si scrive il nome dell’etichetta, seguito da due punti, ed essa si riferirà al byte immediatamente successivo.

Quindi, per esempio, EntryPoint si riferisce al ld a, 0 subito dopo (più precisamente, al primo byte di quell’istruzione, ma ci arriveremo quando ci arriveremo).

Sbirciando all’interno di hardware.inc si vedrà che, per esempio, rNR52 non è definito come un’etichetta.

Il motivo è che queste sono costanti, di cui parleremo più in là; visto che si usano in modo quasi identico alle etichette, per il momento le considereremo uguali.

Scrivere il nome di un’etichetta equivale a scrivere l’indirizzo del byte a cui fa riferimento (con alcune eccezioni che vedremo nella Parte Ⅱ).

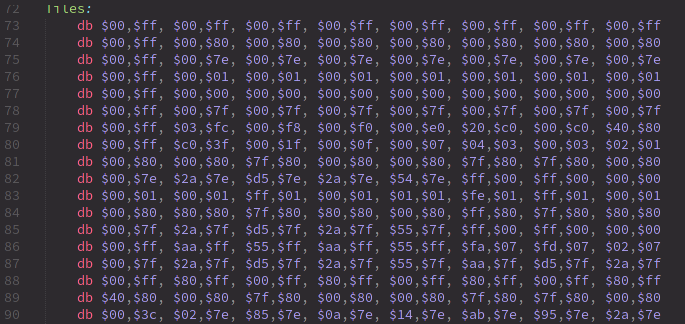

Per esempio, si consideri la ld de, Tiles alla riga 25.

Tiles (riga 64) si riferisce al primo byte dei dati delle mattonelle; se assumiamo che i dati delle mattonelle finiscono per essere memorizzati a partire da $0193, allora ld de, Tiles è equivalente a ld de, $0193!

Cosa sono queste parentesi?

Bene, siamo arrivati a questo punto perché volevamo sapere cosa significano le parentesi in ld a, [de].

In pratica, possono essere lette come “all’indirizzo…”.

Per esempio, ld a, b può essere letto come “copia in a il valore memorizzato in b”; ld a, [$5414] si legge come “copia in a il valore memorizzato all’indirizzo $5414”, e ld a, [de] si legge come “copia in a il valore memorizzato all’indirizzo de”.

Aspettate, cosa significa?

Beh, se de contiene il valore $5414, allora ld a, [de] farà la stessa cosa di ld a, [$5414].

Se avete familiarità con il C, queste parentesi sono sostanzialmente il modo in cui viene implementato l’operatore di dereferenziazione.

hli

I lettori attenti avranno notato il ld [hli], a appena sotto il ld a, [de] che abbiamo appena studiato.

[de] ha senso perché è una delle coppie di registri che abbiamo visto un paio di lezioni fa, ma [hli]?

In realtà, è una notazione speciale, che può essere scritta anche come [hl+].

Funziona come [hl], ma hl viene incrementato subito dopo l’accesso alla memoria.

[hld]/[hl-] è lo specchio di questa, decrementando hl invece di incrementarlo.

Un esempio

Quindi, se osserviamo le prime due istruzioni di CopyTiles:

ld a, [de]

ld [hli], a

…possiamo vedere che stiamo copiando il byte in memoria puntato da de (cioè il cui indirizzo è contenuto in de) nel byte puntato da hl.

Qui, a serve come memoria temporanea, poiché la CPU non è in grado di eseguire direttamente ld [hl], [de].

Già che ci siamo, esaminiamo il resto di .copyTiles nelle lezioni successive!

-

There are other types of memory, such as flash memory or EEPROM, but only Flash has been used on the Game Boy, and for only a handful of games; so we can mostly forget about them. ↩

-

No, really! Mask ROM is created by literally punching holes into a layer of silicon using acid, and e.g. the console’s boot ROM is made of hard-wired transitors within the CPU die. Good luck writing to that!

“ROM” is sometimes (mis)used to refer to “persistent memory” chips, such as flash memory, whose write functionality was disabled. Most bootleg / “repro” Game Boy cartridges you can find nowadays actually contain flash; this is why you can reflash them using specialized hardware, but original cartridges cannot be. ↩

Header

Torniamo a una certa riga all’inizio di hello-world.asm.

ds $150 - @, 0 ; Make room for the header

Che cos’è questo misterioso header, detto anche intestazione? Perché dobbiamo allocargli uno spazio specifico? Queste e tante altre domande troveranno una risposta in questa lezione!

Cos’è l’header?

La prima cosa da fare è spiegare cosa è l’header. È la regione di memoria da $0104 a $014F (inclusa). Contiene metadati sulla ROM, come il titolo, la compatibilità con il Game Boy Color, le dimensioni, due checksum e, cosa interessante, il logo Nintendo che viene visualizzato durante l’animazione di accensione.

Queste e altre informazioni sono disponibili nei documenti Pan.

È interessante notare che la maggior parte delle informazioni contenute nell’header non ha importanza in un hardware reale (la dimensione della ROM è determinata solo dalla capacità del chip ROM nella cartuccia, non dal byte nella intestazione). Difatti, alcuni prototipi di ROM hanno addirittura informazioni errate nell’header!

La maggior parte dell’header veniva utilizzata solo dal reparto di produzione di Nintendo per sapere quali componenti inserire nella cartuccia quando si pubblicava una ROM. Pertanto, solo le ROM inviate a Nintendo dovevano avere una intestazione perfettamente accurata; le ROM utilizzate per i test interni dovevano solo superare i controlli della ROM di avvio, che spiegheremo più avanti.

Tuttavia, nella nostra epoca “moderna”, l’header è molto importante. Gli emulatori (compresi gli emulatori hardware, come le flashcard) devono emulare l’hardware presente nella cartuccia e fanno affidamento su alcuni dei valori presenti nell’header, dato che questa sezione è l’unica fonte di informazioni sull’hardware che la cartuccia della ROM dovrebbe contenere.

ROM di avvio

L’intestazione è profondamente collegata alla cosiddetta boot ROM (ROM di “avvio”).

The most observant and/or nostalgic of you may have noticed the lack of the boot-up animation and the Game Boy’s signature “ba-ding!” in Emulicious. When the console powers up, the CPU does not begin executing instructions at address $0100 (where our ROM’s entry point is), but at $0000.

Tuttavia, in quel momento, un piccolo programma chiamato boot ROM, masterizzato all’interno del silicio della CPU, viene “sovrapposto” alla nostra ROM! La ROM di avvio è responsabile dell’animazione di avvio, ma controlla anche l’intestazione della ROM! In particolare, verifica che i checksum del logo Nintendo e della intestazione siano corretti; se uno dei due controlli fallisce, la ROM di avvio si blocca intenzionalmente e il nostro gioco non verrà mai eseguito :(

For the curious

È possibile trovare una descrizione più dettagliata di ciò che fa la ROM di avvio nei Pan Docs, nonché una spiegazione del controllo del logo. Attenzione, però, perché si tratta di un argomento piuttosto avanzato.

If you want to enable the boot ROMs in Emulicious, you must obtain a copy of the boot ROM(s), whose SHA256 checksums can be found in their disassembly for verification. If you wish, you can also compile SameBoy’s boot ROMs and use those instead, as a free-software substitute.

Then, in Emulicious’ options, go to the Options tab, then Emulation→Game Boy, and choose which of GB and/or GBC boot roms you want to set.

Finally, set the path(s) to the boot ROM(s) you wish to use, and click Open.

Now, just reset the emulator, and voilà!

Un header viene tipicamente definito “valido” se supera i controlli della ROM di avvio e “non valido” in caso contrario.

RGBFIX

RGBFIX è il terzo componente di RGBDS, il cui scopo è scrivere l’header di una ROM. È separato da RGBLINK in modo da poter essere usato come strumento indipendente. Il suo nome deriva dal fatto che RGBLINK di solito non produce una ROM con un header valido, quindi la ROM deve essere “aggiustata” prima di essere pronta per la produzione.

RGBFIX has a bunch of options to set various parts of the header; but the only two that we are using here are -v, which produces a valid header (so, correct Nintendo logo and checksums), and -p 0xFF, which pads the ROM to the next valid size (using $FF as the filler byte), and writes the appropriate value to the ROM size byte.

Guardando altri progetti, si possono trovare invocazioni di RGBFIX con più opzioni, ma queste due dovrebbero essere quasi sempre presenti.

Allora, qual è il problema con questa linea?

Si! Questa linea.

ds $150 - @, 0 ; Make room for the header

Vediamo cosa succede se la rimuoviamo (o la commentiamo).

rgbasm -L -o hello-world.o hello-world.asm

rgblink -o hello-world.gb -n hello-world.sym hello-world.o

(Sto intenzionalmente NON eseguendo RGBFIX; vedremo perché tra poco).

Come ho spiegato, RGBFIX è responsabile della scrittura dell’intestazione, quindi dovremmo usarlo per risolvere questa eccezione.

rgbfix -v -p 0xFF hello-world.gb

warning: Overwrote a non-zero byte in the Nintendo logo

warning: Overwrote a non-zero byte in the header checksum

warning: Overwrote a non-zero byte in the global checksum

Sono sicuro che questi avvisi non sono nulla di cui preoccuparsi… (A seconda della versione di RGBDS in uso, è possibile che siano stati visualizzati avvisi diversi, o addirittura nessuno).

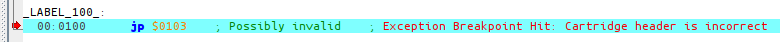

Let’s run the ROM, click on Console on the debugger’s bottom window, press F5 a few times, and…

Ok, allora, cos’è successo?

Come si può vedere dallo screenshot, PC si trova a $0105. Cosa sta facendo lì?

…Oh, EntryPoint è a $0103.

Quindi il jp a $0100 è andato lì e ha iniziato a eseguire le istruzioni (3E CE è la forma grezza di ld a, $CE), ma poi $ED non codifica alcuna istruzione valida, quindi la CPU si blocca.

Ma perché EntryPoint è lì?

Come avrete capito dagli avvisi stampati da RGBFIX, esso sovrascrive l’area dell’header nella ROM.

Tuttavia, RGBLINK non è a conoscenza dell’header (perché RGBLINK non è usato solo per generare ROM!), quindi è necessario riservare esplicitamente spazio per l’area dell’header.

🥴

Dimenticare di riservare questo spazio può far sì che un pezzo di codice o di dati finisca lì e poi venga sovrascritto. Questo è un errore comune di chi è alle prime armi che può lasciare perplessi. Fortunatamente, dalla versione 0.5.1 RGBFIX avverte quando rileva questo errore, come mostrato sopra.

Così, preveniamo disastri come questo:

SECTION "Header", ROM0[$100]

jp EntryPoint

ds $150 - @, 0 ; Make room for the header

La direttiva ds sta per “define space” e consente di riempire un intervallo di memoria.

Questa riga specifica riempie tutti i byte da $103 a $14F (inclusi) con il valore $00.

Poiché parti diverse di codice e/o di dati non possono sovrapporsi, questo assicura che l’intervallo di memoria dell’header possa essere sovrascritto in modo sicuro da RGBFIX e che nessun altro venga accidentalmente sovrascritto.

Potrebbe non essere ovvio come questo ds finisca per riempire quello specifico intervallo di memoria.

Il jp a 3 byte copre gli indirizzi di memoria $100, $101 e $102.

(Iniziamo da $100 perché è dove si trova la SECTION definita manualmente).

Quando RGBASM elabora la direttiva ds, @ (che è un simbolo speciale che valuta “l’indirizzo corrente”) ha quindi il valore $103, quindi riempie $150 - $103 = $4D byte con zeri, quindi $103, $104, …, $14E, $14F.

Bonus: il ciclo infinito

(Questo non è propriamente collegato all’header, ma devo spiegarlo da qualche parte e questo è un posto come un altro)

Ci si potrebbe anche chiedere a cosa serva il ciclo infinito alla fine del codice.

Done:

jp Done

Semplicemente, la CPU non smette mai di eseguire istruzioni; quindi, quando il nostro piccolo Hello World è finito e non c’è più nulla da fare, dobbiamo comunque dare alla CPU un po’ di lavoro: quindi, le facciamo fare nulla, per sempre.

Non possiamo lasciare che la CPU se ne vada, perché inizierebbe a eseguire altre parti della memoria come codice, con il rischio di bloccarsi. (Per verificare: rimuovete o commentate queste due righe, compilate nuovamente la ROM e vedete cosa succede)

Operazioni e flag

Va bene, sappiamo come passare i valori, ma copiare semplicemente i numeri non è divertente; vogliamo modificarli!

La CPU GB non fornisce tutte le operazioni sotto il sole (per esempio, non esiste un’istruzione di moltiplicazione), ma possiamo programmarle da soli con ciò che abbiamo. Parliamo di alcune delle operazioni di cui dispone; per ora ne ometterò alcune non utilizzate in Hello World.

Aritmetica

Le istruzioni aritmetiche più semplici supportate dalla CPU sono inc e dec, che rispettivamente INCrementano e DECrementano il loro operando.

(Se non siete sicuri, “incrementare” significa “aggiungere 1” e “decrementare” significa “sottrarre 1”).

Quindi, per esempio, il dec bc alla riga 32 di hello-world.asm sottrae semplicemente 1 da bc.

Ok, bene!

Possiamo però andare un po’ più veloci?

Certo che sì, con add e sub!

Questi rispettivamente aggiungono e sottraggono valori arbitrari (una costante o un registro).

Nessuno dei due viene usato nel tutorial, ma c’è un parente di sub: avete notato il piccolo cp alla riga 17?

cp permette di confrontare i valori.

Funziona come sub, ma scarta il risultato invece di riscriverlo.

“Aspettate, quindi non fa nulla?”, vi chiederete; beh, aggiorna le flag.

Flag

È arrivato il momento di parlare del registro speciale (ve lo ricordate?) f, per, beh, flag.

Il registro f contiene 4 bit, chiamati “flag”, che vengono aggiornati a seconda dei risultati di un’operazione.

Questi 4 flag sono:

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Z | Zero flag |

| N | Addition/subtraction |

| H | Half-carry |

| C | Carry |

Sì, esistono sia un flag chiamato “C” che un registro chiamato “c” e sono cose diverse e non correlate. Questo rende la sintassi un po’ confusa all’inizio, ma vengono sempre usati in contesti diversi, quindi basta farci caso.

Per ora dimentichiamo N e H; concentriamoci su Z e C. Z è il flag più semplice: viene impostato quando il risultato di un’operazione è 0 e viene azzerato altrimenti. C viene impostato quando un’operazione va in overflow o in underflow.

Che cos’è un overflow?

Prendiamo la semplice istruzione add a, 42.

Questa istruzione aggiunge semplicemente 42 al contenuto del registro a e scrive il risultato in a.

ld a, 200

add a, 42

Alla fine di questo snippet, a è uguale a 200 + 42 = 242, fantastico!

Ma se invece scrivessi questo?

ld a, 220

add a, 42

Si potrebbe pensare che a sia uguale a 220 + 42 = 262, ma non sarebbe corretto.

Ricordate che a è un registro a 8 bit, può memorizzare solo otto bit di informazione!

E se dovessimo scrivere 262 in binario, otterremmo %100000110, che richiede almeno 9 bit…

Quindi cosa succede?

Semplicemente, il nono bit viene perduto e il valore che otteniamo è %00000110 = 6. Questo si chiama overflow.

Questo si chiama overflow: dopo l’aggiunta, otteniamo un valore più piccolo di quello con cui abbiamo iniziato.

We can also do the opposite with sub, and—for example—subtract 42 from 6; as we know, for all X and Y, X + Y - Y = X, and we just saw that 220 + 42 = 6 (this is called modulo 256 arithmetic, by the way); so, 6 - 42 = (220 + 42) - 42 = 220.

This is called an underflow: after subtracting, we get a value greater than what we started with.

Quando viene eseguita un’operazione, imposta il flag di riporto se si è verificato un overflow o un underflow, altrimenti lo azzera. (Vedremo più avanti che non tutte le operazioni aggiornano il flag di riporto)

Summary

- We can add and subtract numbers.

- The Z flag lets us know if the result was 0.

- However, registers can only store a limited range of integers.

- Going outside this range is called an overflow or underflow, for addition and subtraction respectively.

- The C flag lets us know if either occurred.

Confronto

Parliamo ora di come cp viene utilizzato per confrontare i numeri.

Ecco un ripasso: cp sottrae il suo operando da a e aggiorna i flag di conseguenza, ma non scrive il risultato.

Possiamo usare i flag per controllare le proprietà dei valori confrontati e vedremo nella prossima lezione come usarli.

L’interazione più semplice è quella con il flag Z.

Se è impostato, sappiamo che la sottrazione ha prodotto 0, cioè a - operando == 0; quindi, a == operando!

Se non è impostato, allora sappiamo che a != operando.

Ok, controllare l’uguaglianza è bello, ma potremmo anche voler eseguire dei confronti. Non preoccupatevi, perché il flag di riporto serve proprio a questo! Quando si esegue una sottrazione, il flag di riporto viene impostato quando il risultato scende sotto lo 0, ma è solo un modo elegante per dire “diventa negativo”!

Quindi, quando il flag di riporto viene impostato, sappiamo che a - operando < 0 e di conseguenza che a < operando…!

E, al contrario, sappiamo che se non è impostato, a >= operando.

Ottimo!

Riassunto dell’istruzione

| Instruction | Mnemonic | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Add | add | Adds values to a |

| Subtract | sub | Subtracts values from a |

| Compare | cp | Compares values with what’s contained in a |

Jumps

Una volta terminata questa lezione, saremo in grado di capire tutto di CopyTiles!

Finora tutto il codice che abbiamo visto era lineare: veniva eseguito dall’alto verso il basso. Ma questo non è sufficiente: a volte è necessario eseguire alcune azioni in base al risultato di altre (“se le crêpes iniziano ad attaccarsi, ungi di nuovo la padella”), e a volte è necessario eseguire azioni ripetutamente (“se è rimasta della pastella, ripeti dal passo 5”).

Entrambe le cose implicano una lettura non lineare della ricetta. In assembly, questo si ottiene con i salti.

La CPU dispone di un registro speciale chiamato “PC”, che sta per Program Counter. Esso contiene l’indirizzo dell’istruzione in corso di esecuzione1, come se si tenesse a mente il numero del passo della ricetta che si sta eseguendo. Il PC aumenta automaticamente quando la CPU legge le istruzioni, quindi “per impostazione predefinita” vengono lette in sequenza; tuttavia, le istruzioni di salto consentono di scrivere un valore diverso nel PC, saltando di fatto a un’altra parte del programma. Da qui il nome.

Ok, allora parliamo di queste istruzioni di salto, che ne dite? Ce ne sono quattro:

| Instruction | Mnemonic | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Jump | jp | Jump execution to a location |

| Jump Relative | jr | Jump to a location close by |

| Call | call | Call a subroutine |

| Return | ret | Return from a subroutine |

We will focus on jp for now.

jp, such as the one line 5, simply sets PC to its argument, jumping execution there.

In other words, after executing jp EntryPoint (line 5), the next instruction executed is the one below EntryPoint (line 11).

🤔

Ci si potrebbe chiedere a cosa serva questo specifico jp.

Non preoccupatevi, vedremo più avanti perché è necessario.

Salti condizionati

Passiamo ora alla parte davvero interessante. Esaminiamo il ciclo responsabile della copia delle tile:

; Copy the tile data

ld de, Tiles

ld hl, $9000

ld bc, TilesEnd - Tiles

CopyTiles:

ld a, [de]

ld [hli], a

inc de

dec bc

ld a, b

or a, c

jp nz, CopyTiles

Non preoccupatevi se non capite bene quanto segue, perché lo vedremo in azione nella prossima lezione. Se avete problemi, provate ad andare alla prossima lezione e guardate il codice eseguito passo per passo; poi, tornando a questo punto, dovrebbe avere tutto più senso.

Per prima cosa, copiamo Tiles, l’indirizzo del primo byte dei dati delle tile, in de.

Poi, impostiamo hl a $9000, che è l’indirizzo in cui inizieremo a copiare i dati delle tile.

ld bc, TilesEnd - Tiles imposta bc sulla lunghezza dei dati delle tile: TilesEnd è l’indirizzo del primo byte dopo i dati delle tile, quindi sottraendogli Tiles si ottiene la lunghezza.

Quindi, in pratica:

decontains the address where data will be copied from;hlcontains the address where data will be copied to;bccontains how many bytes we have to copy.

Arriviamo quindi al ciclo principale.

Leggiamo un byte dalla sorgente (riga 29) e lo scriviamo nella destinazione (riga 30).

Incrementiamo i puntatori alla destinazione (tramite l’implicito inc hl fatto da ld [hli], a) e alla sorgente (riga 31), in modo che la successiva iterazione del ciclo elabori il byte successivo.

Ecco la parte interessante: poiché abbiamo appena copiato un byte, significa che ne abbiamo uno in meno, quindi dobbiamo fare dec bc.

(Abbiamo già visto dec due lezioni fa; per rinfrescare la memoria, si tratta semplicemente di diminuire di uno il valore memorizzato in bc).

Poiché bc contiene la quantità di byte che devono ancora essere copiati, è facile capire che dobbiamo semplicemente ripetere l’operazione se bc != 0.

😓

dec di solito aggiorna i flag, ma sfortunatamente dec bc non lo fa, quindi dobbiamo controllare manualmente se bc ha raggiunto 0.

ld a, b e or a, c applicano “bitwise OR” a b e c insieme; per ora è sufficiente sapere che lascia 0 in a se e solo se bc == 0.

E or aggiorna il flag Z!

Quindi, dopo la riga 34, il flag Z è impostato se e solo se bc == 0, cioè se dobbiamo uscire dal ciclo.

Ed è qui che entrano in gioco i salti condizionati! È possibile “prendere” condizionatamente un salto a seconda dello stato dei flag.

Le “condizioni” sono quattro:

| Name | Mnemonic | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Zero | z | Z is set (last operation had a result of 0) |

| Non-zero | nz | Z is not set (last operation had a non-zero result) |

| Carry | c | C is set (last operation overflowed) |

| No carry | nc | C is not set (last operation did not overflow) |

Quindi, jp nz, CopyTiles può essere letto come “se il flag Z non è impostato, allora salta a CopyTiles”.

Poiché stiamo saltando all’indietro, ripeteremo di nuovo le istruzioni: abbiamo appena creato un ciclo!

Ok, abbiamo parlato molto del codice e lo abbiamo visto girare, ma non abbiamo visto come gira. Guardiamo la magia che si svolge al rallentatore nella prossima lezione!

-

Not exactly; instructions may be several bytes long, and PC increments after reading each byte. Notably, this means that when an instruction finishes executing, PC is pointing to the following instruction. Still, it’s pretty much “where the CPU is currently reading from”, but it’s better to keep it simple and avoid mentioning instruction encoding for now. ↩

Tracciamento

Avete mai sognato di essere dei maghi? Beh, questo non vi darà poteri magici, ma vediamo come gli emulatori possono essere usati per controllare il tempo!

Per prima cosa, assicuratevi di mettere a fuoco la finestra del debugger.

Spieghiamo innanzitutto il layout del debugger:

In alto a sinistra c’è il visualizzatore del codice, in basso a sinistra c’è il visualizzatore dei dati, in alto a destra ci sono alcuni registri (come abbiamo visto nella lezione sui registri) e in basso a destra c’è il visualizzatore dello stack.

Che cos’è lo stack?

Risponderemo a questa domanda un po’ più avanti… nella Parte Ⅱ 😅

In alto a sinistra c’è il visualizzatore del codice, in basso a sinistra c’è il visualizzatore dei dati, in alto a destra ci sono alcuni registri (come abbiamo visto nella lezione sui registri) e in basso a destra c’è il visualizzatore dello stack.

Che cos’è lo stack?

Risponderemo a questa domanda un po’ più avanti… nella Parte Ⅱ 😅

Preparazione

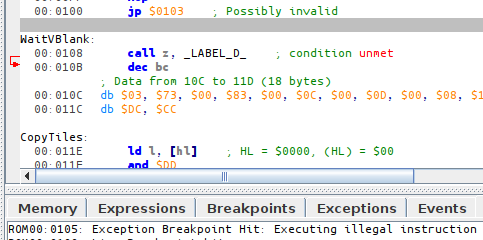

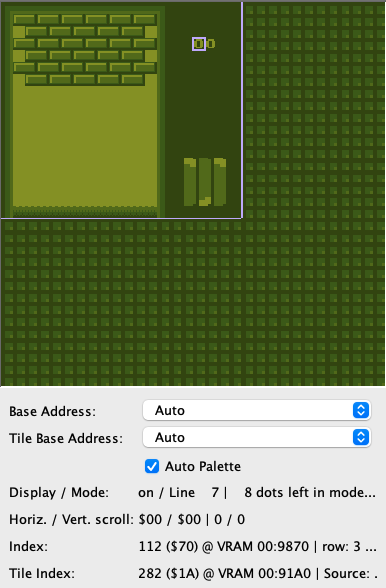

For now, let’s focus on the code viewer.

As Emulicious can load our source code, our code’s labels and comments are automatically shown in the debugger. As we have seen a couple of lessons ago, labels are merely a convenience provided by RGBASM, but they are not part of the ROM itself. In other emulators, it is very much inconvenient to debug without them, and so sym files (for “symbols”) have been developed. Let’s run RGBLINK to generate a sym file for our ROM:

rgblink -n hello-world.sym hello-world.o

‼️

The file names matter!

When looking for a ROM’s sym file, emulators take the ROM’s file name, strip the extension (here, .gb), replace it with .sym, and look for a file in the same directory with that name.

Passo

Quando si mette in pausa l’esecuzione, il debugger si concentra automaticamente sull’istruzione che la CPU sta per eseguire, come indicato dalla riga evidenziata in blu.

ℹ️

The instruction highlighted in blue is always what the CPU is about to execute, not what it just executed. Keep this in mind.

If we want to watch execution from the beginning, we need to reset the emulator. Go into the emulator’s “File” menu, and select “Reset”, or press Ctrl+Backspace.

La linea blu dovrebbe spostarsi automaticamente all’indirizzo $01001 e ora siamo pronti a tracciare! Tutti i comandi per farlo si trovano nel menu “Esegui”.

- “Resume” simply unpauses the emulator.

- “Step Into” and “Step Over” advance the emulator by one instruction.

They only really differ on the

callinstruction, interrupts, and when encountering a conditional jump, neither of which we are using here, so we will use “Step Into”. - The other options are not relevant for now.

We will have to “Step Into” a bunch of times, so it’s a good idea to use the key shortcut.

If we press F5 once, the jp EntryPoint is executed.

And if we press it a few more times, can see the instructions being executed, one by one!

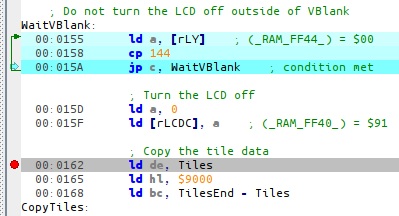

Now, you may notice the WaitVBlank loop runs a lot of times, but what we are interested in is the CopyTiles loop.

We can easily skip over it in several ways; this time, we will use a breakpoint.

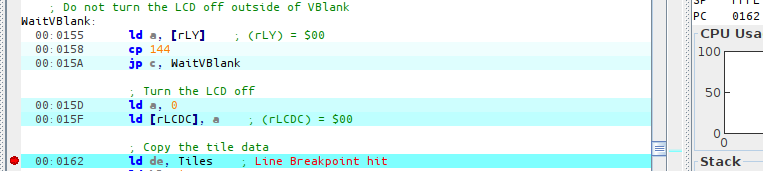

We will place the breakpoint on the ld de, Tiles at 00:0162; either double-click on that line, or select it and press Ctrl+Shift+B.

Then you can resume execution by pressing F8. Whenever Emulicious is running, and the (emulated) CPU is about to execute an instruction a breakpoint was placed on, it automatically pauses.

La freccia verde e il valore di PC indicano il punto in cui l’esecuzione è in pausa.

Se tracciamo le tre istruzioni successive, possiamo vedere che i tre argomenti del ciclo CopyTiles vengono caricati nei registri.

For fun, let’s watch the tiles as they’re being copied. For that, obviously, we will use the Memory Editor, and position it at the destination. As we can see from the image above, that would be $9000!

Click on “Memory” on the bottom window, then “VRAM”, and press Ctrl+G (for “Goto”).

Fantastico, vero?

E poi?

Congrats, you have just learned how to use a debugger! We have only scratched the surface, though; we will use more of Emulicious’ tools to illustrate the next parts. Don’t worry, from here on, lessons will go with a lot more images—you’ve made it through the hardest part!

-

Why does execution start at $0100? That’s because it’s where the boot ROM hands off control to our game once it’s done. ↩

Tile

💭

Le “tile” venivano chiamate in modo diverso nella documentazione di un tempo. Di solito venivano chiamate “schemi” o “caratteri” e quest’ultima ha dato origine all’abbreviazione “CHR”, che a volte viene usata per riferirsi alle tile.

Ad esempio, sul NES, i dati dei tile sono solitamente forniti dalla cartuccia in CHR ROM o CHR RAM. Il termine “CHR” non è tipicamente utilizzato sul Game Boy, anche se gli scambi tra le comunità fanno sì che i termini “trapelino”, per cui alcuni si riferiscono all’area della VRAM in cui sono memorizzati i tile come “CHR RAM” o “CHR VRAM”, ad esempio.

Come per tutti i gerghi di questo tipo, il cui significato può dipendere dall’interlocutore, per coerenza mi atterrò a “tile” in tutto il tutorial, essendo ormai lo standard più diffuso nella comunità degli sviluppatori di GB.

Copiare questi dati alla cieca va benissimo, ma perché i dati sono “grafici”?

Ah, sì, i pixel.

Vediamo un po’!

Un Aiuto

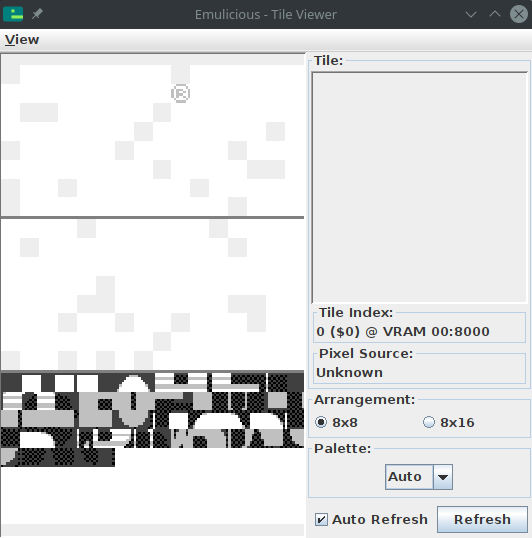

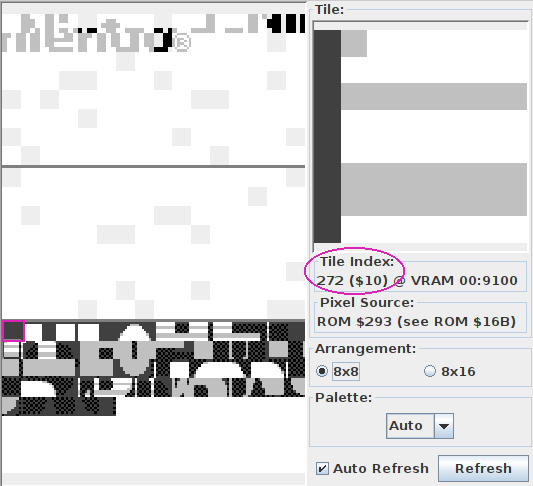

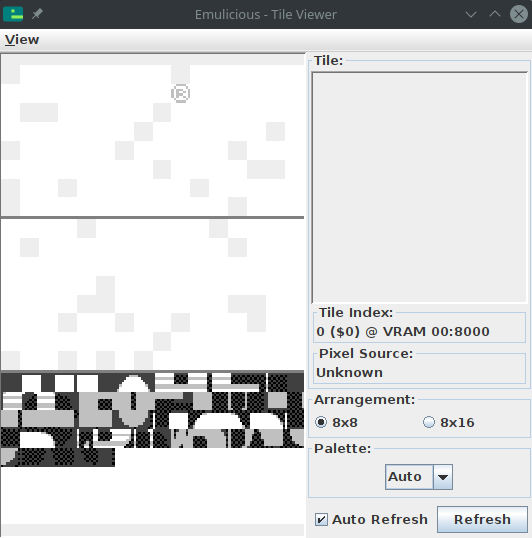

Now, figuring out the format with an explanation alone is going to be very confusing; but fortunately, Emulicious got us covered thanks to its Tile Viewer. You can open it either by selecting “Tools” then “Tile Viewer”, or by clicking on the grid of colored tiles in the debugger’s toolbar.

You can combine the various VRAM viewers by going to “View”, then “Combine Video Viewers”. We will come to the other viewers in due time. This one shows the tiles present in the Game Boy’s video memory (or “VRAM”).

🤔

Vi invito a sperimentare con il visualizzatore di VRAM, a passare il mouse sulle cose, a spuntare e deselezionare le caselle di controllo, a scoprire da soli cosa è cosa. Tutte le domande che vi porrete troveranno risposta a tempo debito, non preoccupatevi! E se quello che vedete in seguito non corrisponde alle mie schermate, assicuratevi di avere le mie stesse caselle spuntate.

Don’t mind the “®” icon in the top-left; we did not put it there ourselves, and we will see why it’s there later.

Primer breve

Potreste aver già sentito parlare di tiles, soprattutto perché erano molto popolari nei sistemi a 8 e 16 bit. Non è una coincidenza: le tile sono molto utili. Invece di memorizzare ogni pixel sullo schermo (144 × 160 pixel × 2 bit/pixel = 46080 bit = 5760 byte, rispetto agli 8192 byte di VRAM della console), i pixel vengono raggruppati in tile, che vengono poi assemblate in vari modi per produrre l’immagine finale.

In particolare, le tile possono essere riutilizzate molto facilmente e praticamente a costo zero, risparmiando molta memoria! Inoltre, la manipolazione di intere tile in una sola volta è molto più economica rispetto alla manipolazione dei singoli pixel e questo fa risparmiare tempo di elaborazione.

Il concetto di “tile” è molto generico, ma sul Game Boy le tile sono sempre di 8 per 8 pixel. Spesso le tile hardware vengono raggruppate per essere manipolate come tile più grandi (spesso 16×16); per evitare la confusione, queste vengono chiamate meta-tile.

“bpp”?

Vi starete chiedendo da dove provenga la cifra di “2 bit/pixel” di cui sopra… Si tratta della cosiddetta “profondità di bit”.

I colori non sono memorizzati nelle tile stesse! Invece, funziona come un libro da colorare: la tile in sé contiene indici di 8 x 8, non colori; si dà all’hardware una tile e un insieme di colori - una tavolozza - e lui li colora! (Questo è anche il motivo per cui le varianti di colore erano molto comuni all’epoca: si potevano creare diverse versioni di un nemico memorizzando piccole tavolozze invece di grandi grafiche diverse.)

In ogni caso, le tavolozze del Game Boy sono grandi 4 colori.1 Ciò significa che gli indici di tali tavolozze, memorizzati nelle tile, possono essere rappresentati con solo due bit! Questo si definisce “2 bit per pixel”, noto come “2bpp”.

Con queste premesse, siamo pronti a spiegare come questi byte si trasformano in pixel!

Codifica

Come ho spiegato, ogni pixel occupa 2 bit. Poiché ci sono 8 bit in un byte, ci si potrebbe aspettare che ogni byte contenga 4 pixel… e non sarebbe né del tutto giusto né del tutto sbagliato. Ogni riga di 8 pixel è memorizzata in 2 byte, ma nessuno di questi byte contiene le informazioni per 4 pixel. (Pensate a una banconota da 10 € strappata a metà: nessuna delle due metà ha valore, ma la banconota intera vale, beh, 10 €).

Per ogni pixel, il bit meno significativo del suo indice è memorizzato nel primo byte, mentre il bit più significativo è memorizzato nel secondo byte. Poiché ogni byte è una raccolta di uno dei bit di ciascun pixel, questo insieme viene chiamato bitplane.

Il pixel più a sinistra è memorizzato nel primo bit da sinistra di entrambi i byte, il pixel alla sua destra nel secondo bit da sinistra e così via. La prima coppia di byte memorizza la riga superiore, il secondo byte quella inferiore e così via.

Ecco una dimostrazione più visiva:

Questa codifica può sembrare un po’ strana all’inizio, e può esserlo; è fatta per essere più conveniente per l’hardware da decodificare, mantenendo la circuiteria semplice e a basso consumo. Rende possibili anche alcuni trucchi interessanti, come vedremo (molto) più avanti!

Si possono trovare ulteriori informazioni sulla codifica nei Pan Docs e nel sito di ShantyTown.

Nella prossima lezione vedremo come si applicano i colori!

-

Other consoles can have varying bit depths; for example, the SNES has 2bpp, 4bpp, and 8bpp depending on the graphics mode and a few other parameters. ↩

Tavolozze

In the previous lesson, I briefly mentioned that colors are applied to tiles via palettes, but we haven’t talked much about those yet.

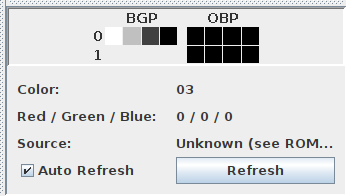

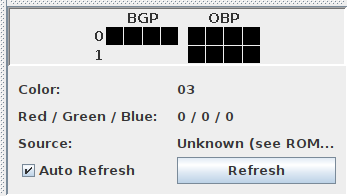

Il Game Boy in bianco e nero ha tre tavolozze, una per lo sfondo chiamata BGP (“BackGround Palette”) e due per gli oggetti chiamate OBP0 e OBP1 (“OBject Palette 0/1”).

Se vi state chiedendo cosa siano gli “oggetti”, dovrete aspettare la Parte Ⅱ per scoprirlo; per ora, concentriamoci sullo sfondo.

🌈

Il Game Boy Color ha introdotto, ovviamente, i colori e questo è stato fatto principalmente rielaborando il modo in cui vengono gestite le tavolozze. Non parleremo delle caratteristiche del Game Boy Color nella Parte Ⅰ per semplicità, ma lo faremo nelle parti successive.

If you chose to combine the video viewers in the previous chapter, the palette viewer should show up on the bottom right of the video viewer.

Otherwise, please select Emulicious’ “Tools” tab, then select Palette Viewer.

Daremo un’occhiata alla linea “BGP”. Come ho spiegato in precedenza, le tile memorizzano gli “indici di colore” per ciascun pixel, i quali vengono utilizzati per indicizzare la tavolozza. Il colore numero 01 è quello più a sinistra in questa riga e il numero 3 è quello più a destra.

Quindi, nel nostro caso, il colore numero 0 è “bianco”, il numero 1 è “grigio chiaro”, il numero 2 è “grigio scuro” e il numero 3 è “nero”. Ho messo le virgolette perché “nero” non è nero puro e “bianco” non è bianco puro. Inoltre, notate che il Game Boy originale aveva sfumature di verde, mentre lo schermo del successivo Game Boy Pocket produceva sfumature di grigio. E, meglio ancora, il Game Boy Color è in grado di colorare automaticamente i giochi che non supportano il Game Boy Color!

Tutto questo per dire che non ci si deve aspettare colori specifici da un gioco per Game Boy2, ma solo quattro colori più o meno luminosi.

Sporchiamoci le mani

In questo tutorial, finora, a parte l’esecuzione di Hello World siamo stati piuttosto passivi, osservando il suo svolgimento. Che ne dite se iniziamo a smuovere un po’ la ROM?

In Emulicious’ debugger, select the “Variables” tab on the left to show the IO registers.

While the VRAM viewer offers a visual representation of the palette, the IO map shows the nitty-gritty: how it’s encoded. The IO map also lets us modify BGP easily; but to do so, we need to understand how values we write are turned into colors.

Codifica

Fortunatamente, la codifica è molto semplice. La spiegherò e allo stesso tempo fornirò un esempio con la tavolozza che abbiamo a portata di mano, $E4.

Take the byte, break its 8 bits into 4 groups of 2.

[BGP] = $E4

$E4 = %11100100 (refresh your memory in the "Binary and hexadecimal" lesson if needed!)

That gets broken down into %11, %10, %01, %00

Il colore numero 0 è il “gruppo” più a destra, il colore numero 3 è quello più a sinistra. Semplice! E questo corrisponde a ciò che ci mostra il visualizzatore VRAM: il colore numero 0, quello più a destra, è quello più chiaro (%00), fino al colore numero 3, che è quello più a sinistra e il più scuro (%11).

Luci spente

Per divertimento, rendiamo lo schermo completamente nero.

Lo si può fare facilmente impostando tutti i colori della tavolozza sul nero (%11).

Questo si traduce in %11 %11 %11 %11 = $FF.

In the “Variables” tab in the debugger, click on the byte to the right of BGP, erase the “E4”, type “FF”, and hit Enter. BGP immediately updates, turning the screen black!

E se volessimo prendere la tavolozza originale, ma invertirla? %11 diventerebbe %00, %01 diventerebbe %10, %10 diventerebbe %01 e %00 diventerebbe %11. Otterremmo così:

%11_10_01_00

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

%00_01_10_11

(Non fornirò il valore in esadecimale, usate questa opportunità per esercitare le vostre conversioni da bin a esadecimale!)

If you go to the Tile Viewer and change “Palette” to “Gray”, you will notice that the tile data stays the same regardless of how the palette is modified! This is an advantage of using palettes: fading the screen in and out is very cheap, just modifying a single byte, instead of having to update every single on-screen pixel.

Avete capito tutto? Allora diamo un’occhiata all’ultimo pezzo mancante del puzzle nel processo di rendering di Hello World, la tilemap!

-

Numbering often starts at 0 when working with computers. We will understand why later, but for now, please bear with it! ↩

-

Well, it is possible to detect these different models and account for them, but this would require taking plenty of corner cases into consideration, so it’s probably not worth the effort. ↩

Tilemap

🧐

Alcuni li chiamano “tile map”, altri “tilemap”.

Io userò quest’ultimo di preferenza, ma lo userò anche nel codice (Tilemap e non TileMap), così come più avanti quando parleremo di mappe di attributi (“attrmap” e Attrmap invece di AttrMap).

Ci siamo quasi. Abbiamo visto come la grafica del Game Boy sia composta da “tessere” 8×8 e come il colore venga aggiunto al mix.

Ma non abbiamo ancora visto come queste tessere vengono disposte in un’immagine finale!

Tiles are basically a grid of pixels; well, the tilemaps are basically a grid of tiles! To allow for cheap reuse, tiles aren’t stored in the tilemap directly; instead, tiles are referred to by an ID, which you can see in Emulicious’ Tile Viewer.

Naturalmente gli ID delle tessere sono numeri, come tutti i computer. Gli ID sono memorizzati in byte, quindi ci sono 256 possibili ID di piastrelle. Tuttavia, il lettore più attento avrà notato che ci sono 384 tessere in totale[^blocchi_di_tile]! In virtù del principio della piccionaia, ciò significa che alcuni ID si riferiscono a più piastrelle contemporaneamente.

Indeed, Emulicious reports that the first 128 tiles have the same IDs as the last 128. There exists a mechanism to select whether IDs 0–127 reference the first or last 128 tiles, but for simplicity’s sake, we will overlook this for now, so please ignore the first (topmost) 128 tiles for the time being.

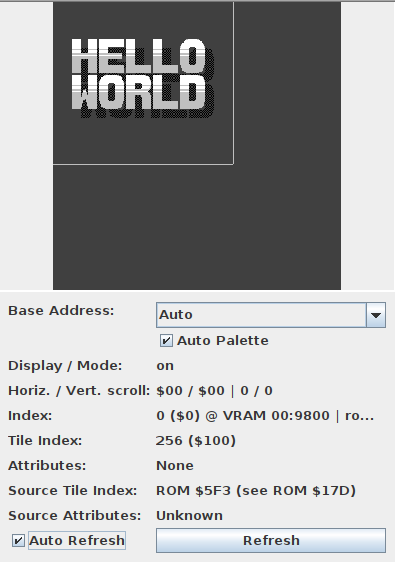

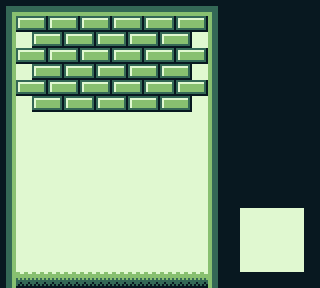

Now, please turn your attention to Emulicious’ Tilemap Viewer, pictured below.

You may notice that the image shown is larger than what is displayed on-screen. Only part of the tilemap, outlined by a thicker border in the Tilemap Viewer, is displayed on-screen at a given time. We will explain this in more detail in Part Ⅱ.

Qui potremo vedere la potenza del riutilizzo dei tile in tutta la sua forza. Per comodità e per rinfrescare la memoria, ecco le tessere che il nostro Hello World carica nella VRAM:

Si può notare che abbiamo caricato una sola tessera “vuota” ($00, la prima a sinistra in alto), ma può essere ripetuta per coprire l’intero sfondo senza costi aggiuntivi!

La ripetizione può essere più sottile: ad esempio, la tessera $01 è utilizzata per l’angolo superiore sinistro di H, E, L, L e W (linee rosse in basso)! Anche la R, la L e la D condividono la loro tessera in alto a sinistra ($2D, linee blu in basso); e così via. È possibile confermarlo passando il mouse sulle tessere nella scheda BG map, che mostra l’ID della tessera in quella posizione.

Tutto sommato, possiamo dedurre che la visualizzazione della grafica sul Game Boy consiste nel caricare i “modelli” (le tessere) e nel dire alla console quale tessera visualizzare per ciascuna posizione.

In conclusione